Clearly, and as the IEA points out, global energy demand grew faster last year, even with continued electrification of transport, because of a number of key factors:

- Climate change is causing changes to the world’s climate, with colder winters and hotter summers requiring more energy than normally for heating and cooling

- Data centres are springing up everywhere with voracious needs for more energy. And this is only the beginning

- The GDP per capita of the most populous countries in the world, India and China, but also that of Africa, is growing fast and so are their energy needs

- World population is expected to increase by 20% by 2050 and with it so will global energy demand.

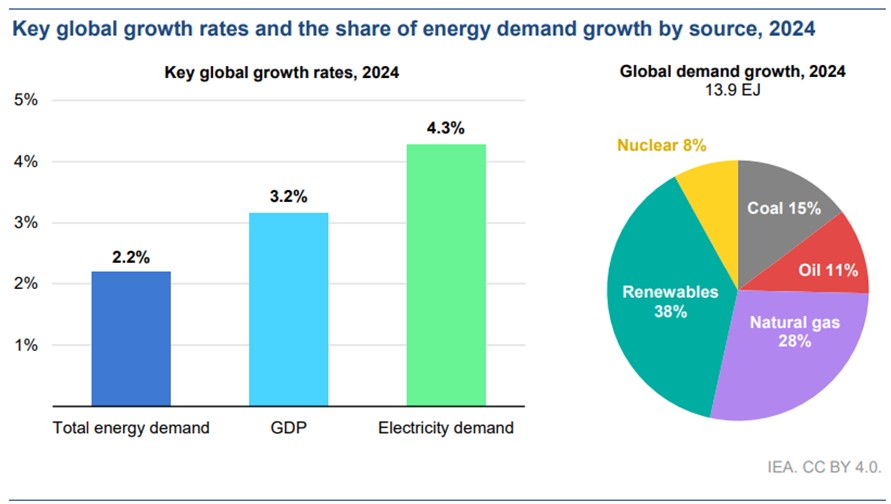

These are long-term factors that are now causing global energy demand to increase at a faster rate, impacting energy transition, as evidenced in IEA’s report. It increased by 2.2% in 2024, a much faster rate when compared to the 1.3%average during the previous ten years.

The rapid increase in renewables was not sufficient to provide this.It required all energy sources,coal, oil, natural gas, renewables, and nuclear, to grow in 2024 (Figure 1). A trend likely to continue into the foreseeable future.

Figure 1: Global energy growth rates in 2024

What is interesting is the slant placed on this by the IEA. Fatih Birol, executive director IEA, said “What is certain is that electricity use is growing rapidly, pulling overall energy demand along with it to such an extent that it is enough to reverse years of declining energy consumption in advanced economies. The result is that demand for all major fuels and energy technologies increased in 2024,” but electricity demand increased by a whopping 4.3%.In reality it is the other way round. Total energy is growing at a faster rate, driven by India and China, and with it so is demand for all fuels, including electricity.

As a proportion of total energy supply, electricity changed only but a little: 16.9% in 2022, 17.0% in 2023 and 17.3% in 2024. Fossil fuels still provide over 80% of total energy, only slightly less than the average of the previous ten years.

The growth in renewable energy is undoubtedly fast and rightly so as the world strives to contain and reduce emissions. But overstating the impact of this on total energy, as the IEA does, is unnecessary and undermines credibility.

With total energy now growing at a faster rate, unless current renewables and electricity growth rates increase dramatically, their contribution will take a long time to make a major difference.

Emissions

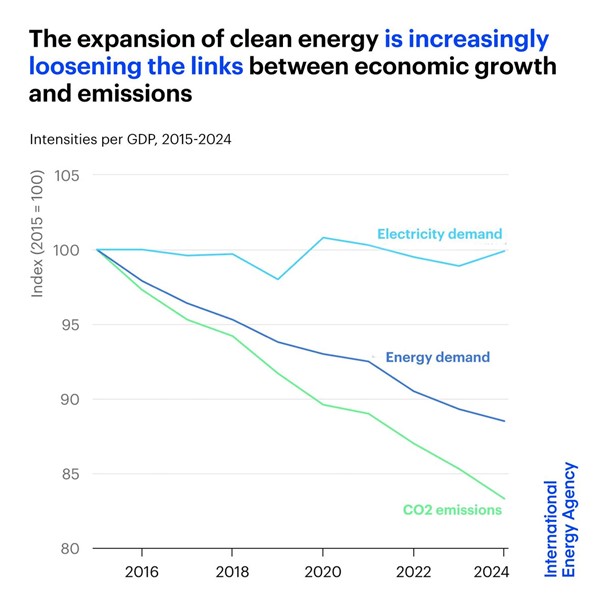

The IEA states that “for many decades, economic growth has been closely tied to a rise in greenhouse gas emissions. But the expansion of clean energy is increasingly loosening the links between economic growth and emissions.”

The IEAsupports this by comparing energy demandand CO2 emission intensities per GDP between 2015-2024 (Figure 2).These have declined significantly since 2015 as a result of efficiency gains.

Figure 2: Energy demand, electricity demand and CO2 emission intensities per GDP between 2015-2024

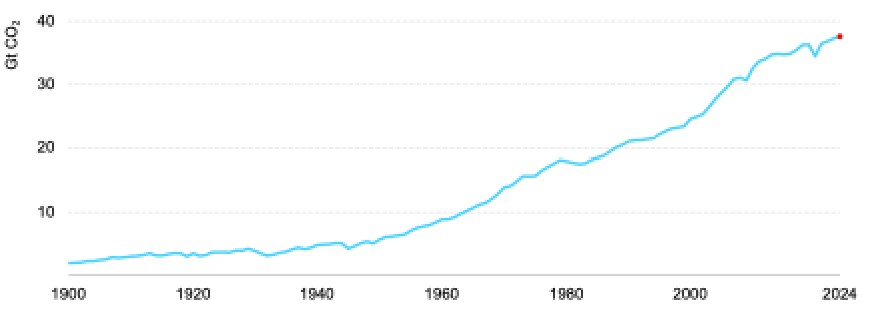

But despite these declining intensities, total energy-related CO2 emissions have been increasing steadily, and since the 1950s at a more or less constant rate (Figure 3), similar to the rate of growth of global energy demand.

Figure 3: Global energy-related CO2 emissions, 1900-2024

Indeed, the ratio (Emission index reduction)/(Energy demand index reduction) has remained pretty much constant at about 1.4 since 2015, confirming that, so far, emissions change in tandem with energy demand.

To conclude from these results that emission growth is decoupling from GDP growth is stretching interpretation of data. That may have been so in advanced economies, but not in the rest of the world. But in 2024, following years of limited or no growth, energy demand also increased in advanced economies, a trend that may be here to stay.

Incidentally, actual CO2 emissions at the end of 2024 were 37.8 Gt CO2, much higher than those estimated by all scenarios in IEA’s ‘World Energy Outlook 2020’, including the STEPS estimate of 35.4 Gt CO2.

Other than in IEA scenarios, based on increasingly out-of-reach pre-determined outcomes, business-as-usual indicates that the link between future growth in energy demand and energy-related emissions will continue into the foreseeable future and will be driven by emerging and developing economies, with no sign of peaking trends. Increasing population needs and aspirations for improved living standards take priority over energy transition.

Business as usual?

In a bombshell report, Morgan Stanley, JPMorgan Chase and the US Institute of International Finance predict climate goals will fail. The US finance sector "considers the Paris climate agreement limiting global temperatures...is effectively dead and investors should plan accordingly.” They say “progress on climate change is likely to fall short of net-zero targets” and that “we now expect a 3oC world.” This comes just months after they first weakened their decarbonization targets and then quit the ‘Net Zero Banking Alliance’.

The EU is also reconsidering its green energy policies in its drive to improve competitiveness. In effect the EU is aiming its ‘simplification’ sledgehammer at green energy laws. This has come as a result of growing criticism of European Commission’s European Green Deal, which aims to make the EU climate-neutral by 2050, but it is now considered to be too burdensome and to have impacted Europe’s competitiveness.

Energy transition is faltering. What we are into is energy addition, in which all forms of energy are still needed.

These developments put into question IEA’s STEPSand other scenarios. Even though useful in terms of “understanding possible energy futures”, the question is how realistic are these in terms of indicating where global energy and climate change are going as the world approaches 2030 and beyond. A much more realistic scenario would be ‘business-as-usual’, at least as far as the foreseeable future is concerned, that, so far, the IEA avoids presenting.

*Dr Charles Ellinas, @CharlesEllinas

Councilor

Atlantic Council

8 April, 2025